One fundamental idea that has endured throughout the years in the large field of investing is strategic asset allocation. Strategic asset allocation has become an effective method that is embraced by seasoned investors and financial experts, rather than just being a trendy term. Strategic asset allocation may be the key to maximizing your investment potential when it comes to managing your investment portfolio.

However, what precisely is strategic asset allocation, and why is it regarded as the foundation of profitable investing?

Table of Content

- What is Asset Allocation?

- Importance of Asset Allocation in Investment Strategy

- Understanding Asset Classes

- Modern Portfolio Theory

- Strategic vs. Tactical Asset Allocation

- Risk Tolerance and Investment Goals

- Implementing Asset Allocation

- Asset Allocation in Different Life Stages

What is Asset Allocation?

The division of an investor’s portfolio among various assets, such as stocks, fixed-income securities, cash, and its equivalents, is known as asset allocation. Based on their financial objectives, risk tolerance, and investment horizon, investors typically seek to strike a balance between rewards and risks.

Financial advisors typically encourage investors to diversify their investments over a range of asset classes in order to lower the level of volatility in their portfolios. Because different asset classes will always yield different returns, asset allocation is a common strategy in portfolio management because of this fundamental rationale. As a result, investors will get protection from their investments depreciating.

When making investment decisions, an investor’s portfolio distribution is influenced by factors such as personal goals, level of risk tolerance, and investment horizon.

1. Goal factors

Goal factors are individual aspirations to achieve a given level of return or saving for a particular reason or desire. Therefore, different goals affect how a person invests and risks.

2. Risk tolerance

Risk tolerance refers to how much an individual is willing and able to lose a given amount of their original investment in anticipation of getting a higher return in the future. For example, risk-averse investors withhold their portfolios in favor of more secure assets. In contrast, more aggressive investors risk most of their investments in anticipation of higher returns.

3. Time horizon

The time horizon factor depends on the duration an investor is going to invest. Most of the time, it depends on the goal of the investment. Similarly, different time horizons entail different risk tolerance.

For example, a long-term investment strategy may prompt an investor to invest in a more volatile or higher-risk portfolio since the dynamics of the economy are uncertain and may change in favor of the investor. However, investors with short-term goals may not invest in riskier portfolios.

Importance of Asset Allocation in Investment Strategy

There’s no formula for the right asset allocation for everyone, but the consensus among most financial professionals is that asset allocation is one of the most important decisions investors make. Selecting individual securities within an asset class is done only after you decide how to divide your investments among stocks, bonds, and cash and cash equivalents. This will largely determine your investment results.

Investors use different asset allocations for distinct goals. Someone saving to buy a new car in the next year might invest those savings in a conservative mix of cash, certificates of deposit, and short-term bonds. However, individuals saving for retirement decades away typically invest most of their retirement accounts in stocks because they have a lot of time to ride out the market’s short-term fluctuations.

Understanding Asset Classes

An asset class is a collection of investments that share traits and are governed by the same rules and laws. As a result, instruments that frequently exhibit comparable market behavior make up asset classes. Equities, fixed income, commodities, and real estate are a few common asset classes.

An asset class is, to put it simply, a collection of similar financial products. As an illustration, the equities IBM, MSFT, and AAPL are grouped together. Asset class categories and classes are frequently combined. Across multiple asset classes, there is typically relatively little correlation and occasionally a negative correlation. In the world of finance, this quality is crucial.

Historically, the three main asset classes have been equities (stocks), fixed income (bonds), and cash equivalent or money market instruments. Currently, most investment professionals include real estate, commodities, futures, other financial derivatives, and even cryptocurrencies in the asset class mix. Investment assets include both tangible and intangible instruments that investors buy and sell for the purposes of generating additional income, on either a short- or long-term basis.

Financial advisors view investment vehicles as asset-class categories that are used for diversification purposes. Each asset class is expected to reflect different risk and return investment characteristics and perform differently in any given market environment. Investors interested in maximizing return often do so by reducing portfolio risk through asset class diversification.

Financial advisors will help investors diversify their portfolios by combining assets from different asset classes that have different cash flow streams and varying degrees of risk. Investing in several different asset classes ensures a certain amount of diversity in investment selections. Diversification reduces risk and increases your probability of making a positive return.

The most common asset classes are:

Cash and Cash Equivalents

Cash and cash equivalents represent actual cash on hand and securities that are similar to cash. This type of investment is considered very low risk since there is little to no chance of losing your money. That peace of mind means the returns are also lower than other asset classes.

Examples of cash and cash equivalents include cash parked in a savings account as well as U.S. government Treasury bills (T-bills), guaranteed investment certificates (GICs), and money market funds. Generally, the greater the risk of losing money, the greater the prospective return.

Fixed Income

Fixed income is an investment that pays a fixed income. Basically, you lend money to an entity and, in return, they pay you a fixed amount until the maturity date, which is the date when the money you initially invested (the loan) is paid back to you.

Government and corporate bonds are the most common types of fixed-income products. The government or company will pay you interest for the life of the loan, with rates varying depending on inflation and the perceived risk that they won’t make good on the loan. The risk of certain governments defaulting on their bonds is very unlikely, so they pay out less. Conversely, some companies risk going bust and need to pay investors more to convince them to part with their money.

Equities

When people talk about equities, they are usually speaking about owning shares in a company. For companies to expand and meet their objectives, they often resort to selling slices of ownership in exchange for cash to the general public. Buying these shares represents a great way to profit from the success of a company.

There are two ways to make money from investing in companies:

- If the company pays a dividend

- If you sell the shares for more than you paid for them

The market can be volatile, though. Share prices are known to fluctuate, and some companies may even go bust.

Commodities

Commodities are basic goods that can be transformed into other goods and services. Examples include metals, energy resources, and agricultural goods.

Commodities are crucial to the economy and, in some cases, are viewed as a good hedge against inflation. Their return is based on supply and demand dynamics rather than profitability. Many investors invest indirectly in commodities by buying shares in companies that produce them. However, there is also a huge market for investing directly, whether that is actually buying a physical commodity with the view of eventually selling it for a profit or investing in futures.

Equities (stocks), bonds (fixed-income securities), cash or marketable securities, and commodities are the most liquid asset classes and, therefore, the most quoted asset classes.

There are also alternative asset classes, such as real estate, and valuable inventory, such as artwork, stamps, and other tradable collectibles. Some analysts also refer to an investment in hedge funds, venture capital, crowdsourcing, or cryptocurrencies as examples of alternative investments. That said, an asset’s illiquidity does not speak to its return potential; it only means that it may take more time to find a buyer to convert the asset to cash.

Modern Portfolio Theory

The modern portfolio theory (MPT) is a practical method for selecting investments in order to maximize their overall returns within an acceptable level of risk. This mathematical framework is used to build a portfolio of investments that maximize the amount of expected return for the collective given level of risk.

American economist Harry Markowitz pioneered this theory in his paper “Portfolio Selection,” which was published in the Journal of Finance in 1952. He was later awarded a Nobel Prize for his work on modern portfolio theory.

A key component of the MPT theory is diversification. Most investments are either high risk and high return or low risk and low return. Markowitz argued that investors could achieve their best results by choosing an optimal mix of the two based on an assessment of their individual tolerance to risk.

The modern portfolio theory argues that any given investment’s risk and return characteristics should not be viewed alone but should be evaluated by how it affects the overall portfolio’s risk and return. That is, an investor can construct a portfolio of multiple assets that will result in greater returns without a higher level of risk.

As an alternative, starting with a desired level of expected return, the investor can construct a portfolio with the lowest possible risk that is capable of producing that return. Based on statistical measures such as variance and correlation, a single investment’s performance is less important than how it impacts the entire portfolio.

The MPT is a useful tool for investors who are trying to build diversified portfolios. In fact, the growth of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) made the MPT more relevant by giving investors easier access to a broader range of asset classes.

For example, stock investors can reduce risk by putting a portion of their portfolios in government bond ETFs. The variance of the portfolio will be significantly lower because government bonds have a negative correlation with stocks. Adding a small investment in Treasuries to a stock portfolio will not have a large impact on expected returns because of this loss-reducing effect.

Harry Markowitz and the Birth of Modern Portfolio Theory

Harry Markowitz is an American economist and creator of the influential Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) still widely used today. Harry Markowitz was born in Chicago, Illinois, on August 24, 1927. After completing his bachelor’s in philosophy at the University of Chicago, Markowitz returned to the university for a master’s in economics, studying under influential economists such as Milton Friedman.

While writing his dissertation on the application of mathematics to stock market analysis, Markowitz took great interest in John Burr Williams’ “Theory of Investment Value.” Williams emphasized investors’ consideration of the expected value of assets within the portfolio, but Markowitz realized the argument lacked considerations of risk.

Markowitz identified the risk as variance – the measurement of volatility from the mean. Furthermore, he determined that investors could benefit from diversifying their portfolio due to idiosyncratic risk. Idiosyncratic risk is the risk inherent in specific assets. By incorporating different assets into a portfolio, diversification removes such a risk if the assets show low covariance (correlation of movement between assets).

Using risk and return as the primary considerations of investors, Markowitz pioneered the modern portfolio theory (MPT), published in 1952 by the Journal of Finance. He continued his work with colleague George Dantzig, where he refined his research on optimal portfolio allocation. His resulting work on graphing the Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) would later be named the efficient frontier. He went on to receive a Ph.D. in economics and published his new findings on portfolio allocation.

His work earned him the John von Neumann Theory Prize in 1989 and the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1990. Almost a decade after Markowitz’s initial publication on MPT, the famous capital asset pricing model (CAPM) was introduced, based on Markowitz’s theory of risk and diversification.

Currently, Harry Markowitz spends his time teaching at the University of California San Diego and consulting at Harry Markowitz Company.

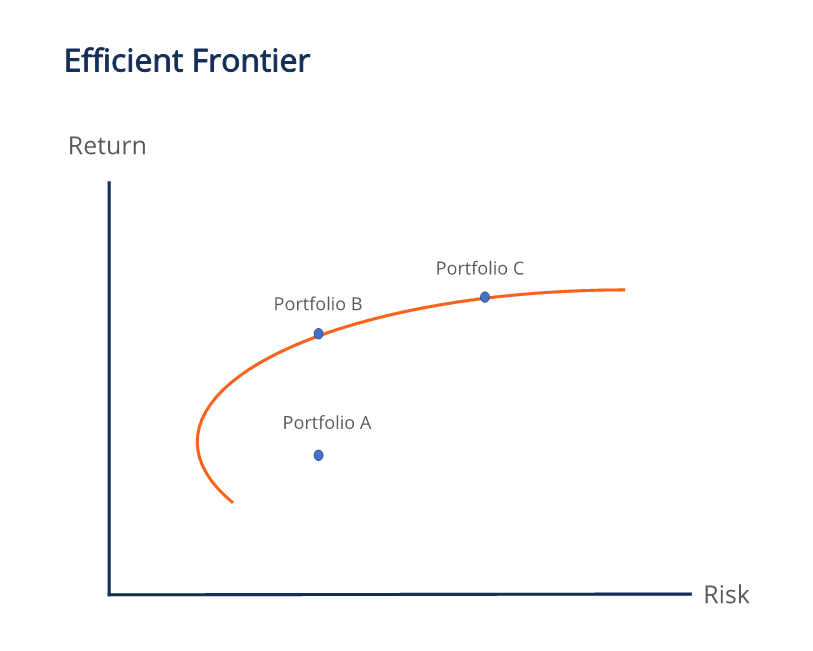

Efficient Frontier

The theory states that a portfolio’s risk can be reduced through diversification. Diversification works by holding many different assets with low or negative covariance. The low/negative covariance reduces the volatility (risk) of the portfolio by eliminating the idiosyncratic risk inherent in individual securities. The MPT takes an aggregate view in that each asset is less important than its impact on the portfolio as a whole.

The theory assumes that investors are risk-averse, meaning that between two portfolios with the same risk, investors prefer the one with a higher return. Because individual investors have different risk tolerances, Markowitz developed the efficient frontier, where each point along the curve represents the optimal asset weightings in a portfolio that gives the highest expected return for the amount of risk. The graph depicts expected return as a function of risk.

Portfolios towards the right are weighted heavier on risky assets such as stocks and private equity. Portfolios towards the left are weighted heavier on less risky assets such as bonds. The upwards shape of the efficient frontier demonstrates the concept that higher risk comes with a higher return.

Any portfolios on the efficient frontier are better than those under it. In the illustration above, portfolio B is objectively better than portfolio A because it has a higher expected return than portfolio A for the same risk. Such portfolios on the efficient frontier are called the Markowitz efficient set.

The best portfolio allocation on the efficient frontier depends on the level of risk tolerance of the investor. Both portfolio B and portfolio C have the highest return for their given risk. Therefore, we cannot say one is better than the other; investors with higher risk tolerance will like C better, while more conservative investors will like B better.

Capital Market Line

The capital market line (CML) shows portfolios with the best possible balance between return and risk. It is a theoretical idea that stands for all possible combinations of the market portfolio of risky assets and the risk-free rate of return. As this maximizes profit for a given degree of risk, all investors will, according to the capital asset pricing model (CAPM), take an equilibrium position on the capital market line by lending or borrowing at the risk-free rate.

Portfolios that fall on the capital market line (CML), in theory, optimize the risk/return relationship, thereby maximizing performance. The capital allocation line (CAL) makes up the allotment of risk-free assets and risky portfolios for an investor.

CML is a special case of the CAL where the risk portfolio is the market portfolio. Thus, the slope of the CML is the Sharpe ratio of the market portfolio. As a generalization, buy assets if the Sharpe ratio is above the CML and sell if the Sharpe ratio is below the CML.

Mean-variance analysis was pioneered by Harry Markowitz and James Tobin. The efficient frontier of optimal portfolios was identified by Markowitz in 1952, and James Tobin included the risk-free rate to modern portfolio theory in 1958. William Sharpe then developed the CAPM in the 1960s, and won a Nobel prize for his work in 1990, along with Markowitz and Merton Miller.

The CAPM is the line that connects the risk-free rate of return with the tangency point on the efficient frontier of optimal portfolios that offer the highest expected return for a defined level of risk, or the lowest risk for a given level of expected return.

The portfolios with the best trade-off between expected returns and variance (risk) lie on this line. The tangency point is the optimal portfolio of risky assets, known as the market portfolio. Under the assumptions of mean-variance analysis—that investors seek to maximize their expected return for a given amount of variance risk, and that there is a risk-free rate of return—all investors will select portfolios that lie on the CML.

According to Tobin’s separation theorem, finding the market portfolio and the best combination of that market portfolio and the risk-free asset are separate problems. Individual investors will either hold just the risk-free asset or some combination of the risk-free asset and the market portfolio, depending on their risk aversion.

As an investor moves up the CML, the overall portfolio risk and returns increase. Risk-averse investors will select portfolios close to the risk-free asset, preferring low variance to higher returns. Less risk-averse investors will prefer portfolios higher up on the CML, with a higher expected return, but more variance. By borrowing funds at a risk-free rate, they can also invest more than 100% of their investable funds in the risky market portfolio, increasing both the expected return and the risk beyond that offered by the market portfolio.

Strategic vs. Tactical Asset Allocation

Making the decision to allocate assets in a strategic or tactical manner throughout the construction of an investment portfolio is significant. Which, though, is better for your investments? The response is based on your objectives and particular financial condition. Also, your investing approach will benefit from your grasp of the differences. This is an explanation and contrast of the distribution of assets, tactical and strategic.

Strategic Asset Allocation

With this approach, you won’t be chasing trends to time the market. Instead, the goal is to create and maintain a portfolio with an appropriate mix of assets to reach your goals. Of course, the appropriate mix of assets will vary widely based on your unique investment goals and risk tolerance.

Read Also: The Ultimate Guide to Dividend Investing for Long-Term Wealth

A common strategic asset allocation includes a 60/40 portfolio. In this asset allocation strategy, you would have 60% of your assets in stocks and 40% in bonds. No matter the mix of assets, you’ll choose a strategy that you want to stick to for the long term. So, if the market goes up and down, you don’t plan to make adjustments to your strategy along the way. But you may rework your strategy if your risk tolerance changes.

Beyond a portfolio with asset allocations that include a long-term outlook, a strategic asset allocation also requires rebalancing to maintain the strategy. Without regular rebalancing, it is all too easy for the target asset allocations to move away from your goals.

Tactical Asset Allocation

In contrast, a tactical asset allocation strategy takes a more active approach that responds to changing market conditions. Although you may have a long-term strategy in place, you regularly make changes along the way for short-term returns.

With a tactical asset allocation, your goal is to maximize your portfolio’s performance. Instead of sticking to a long-term strategy, a tactical asset allocation means that you will make changes to your portfolio based on the market conditions.

When pursuing a tactical asset allocation, chasing down great market deals takes a lot more time and effort than a strategic asset allocation. Additionally, the cost of more regular trading could cut into your returns.

The right asset allocation varies based on your goals. Plus, you’ll need to consider the amount of time tied to each strategy. Let’s break down who is best suited for a strategic asset allocation:

- New investors that want to set up a relatively passive approach

- Buy and hold investors who want their portfolio to grow with the market

- Young investors with plenty of time to recover from any downturns

- New investors seeking a relatively simple way to diversify

- Investors who know sticking to a plan is important

A strategic asset allocation can help you stick to a long-term investment plan. And that’s a big deal. Without a plan in place, many investors are prone to making emotional decisions with the market sees a big dip.

The unfortunate reality is that the stock market has inherent volatility. And with that, investors should be prepared to see big swings throughout their long investment horizon. By setting up a strategic asset allocation upfront, it can be easier to stick to a long-term plan.

Now, let’s compare who is best suited for tactical asset allocation:

- Experienced investors who have the time and energy to monitor and act on market trends

- Investors seeking to maximize their portfolio returns

- Experienced investors with in-depth market knowledge

- Investors seeking portfolio flexibility

Keeping up with a tactical asset allocation isn’t the right move for a hands-off investor. But if you have the time and inclination to seek out opportunities for portfolio growth, a tactical strategy can be a good idea.

When building a portfolio, the right asset allocation is important. The choice between a strategic vs tactical asset allocation should be straightforward. You either want to stick to a predetermined plan based on your risk tolerance or have the flexibility to make changes based on the market conditions.

Risk Tolerance and Investment Goals

When constructing an investment portfolio or a thorough financial plan, risk tolerance is one of the most crucial factors, if not the most crucial one. An investor’s risk tolerance, which manifests in practise as their willingness and aptitude to take investment risks, is their capacity to tolerate variability in portfolio returns.

Older investors typically have a lesser tolerance for risk. Considering their longer projected time horizons, younger investors can typically take on more risk. This is by no means an inflexible rule, though. Each person’s specific risk tolerance needs to be assessed.

Risk tolerance is your ability to handle portfolio volatility. In this context, it’s more concerned with large negative movements since people are able to handle positive investment returns quite well.

Risk tolerance can be influenced by a number of factors, including goals, age, degree of portfolio reliance, personal comfort, and absolute net worth.

- 1. Timeline

Each investor will adopt a different time horizon based on their investment plans. Generally, more risk can be taken if there is more time. An individual who needs a certain sum of money at the end of fifteen years can take more risk than an individual who needs the same amount by the end of five years. It is due to the fact that the market has shown an upward trend over the years. However, there are constant lows in the short term.

- 2. Goals

Financial goals differ from individual to individual. To accumulate the highest amount of money possible is not the sole purpose of financial planning for many. The amount required to achieve certain goals is calculated, and an investment strategy to deliver such returns is usually pursued. Therefore, each individual will take on a different risk tolerance based on goals.

- 3. Age

Usually, young individuals should be able to take more risks than older individuals. Young individuals have the capability to make more money working and have more time on their hands to handle market fluctuations.

- 4. Portfolio size

The larger the portfolio, the more tolerance to risk. An investor with a $50 million portfolio will be able to take more risk than an investor with a $5 million portfolio. If value drop, the percentage loss is much less in a larger portfolio when compared to a smaller portfolio.

- 5. Investor comfort level

Each investor handles risk differently. Some investors are naturally more comfortable with taking risks than others. On the contrary, market volatility can be extremely stressful for some investors. Risk tolerance is, therefore, directly related to how comfortable an investor is while taking risks.

Types of Risk Tolerance

Investors are usually classified into three main categories based on how much risk they can tolerate. The categories are based on many factors, a few of which have been discussed above. The three categories are:

- 1. Aggressive

Aggressive risk investors are well-versed in the market and take huge risks. Such types of investors are used to seeing large upward and downward movements in their portfolios. Aggressive investors are known to be wealthy, experienced, and usually have a broad portfolio.

They prefer asset classes with a dynamic price movement, such as equities. Due to the amount of risk they take, they reap superior returns when the market is doing well and naturally face huge losses when the market performs poorly. However, they do not panic sell at times of crisis in the market as they are used to fluctuations on a daily basis.

- 2. Moderate

Moderate-risk investors are relatively less risk-tolerant when compared to aggressive-risk investors. They take on some risk and usually set a percentage of losses they can handle. They balance their investments between risky and safe asset classes. With the moderate approach, they earn less than aggressive investors when the market does well but do not suffer huge losses when the market falls.

- 3. Conservative

Conservative investors take the least risk in the market. They do not indulge in risky investments at all and go for the options they feel are safest. They prioritize avoiding losses above making gains. The asset classes they invest in are limited to a few, such as FD and PPF, where their capital is protected.

Short-term and Long-term Financial Goals

Although saving money is important, it should also be a conscious decision. The kinds of goals you’re saving for will determine how and how much you save. Over your life, those objectives will undoubtedly change, but the tactics you pick up won’t.

Savings goals can be broadly classified into two categories: short-term and long-term. Long-term objectives are often five years or more in the future, and short-term goals are ones you hope to accomplish in a few years.

Short-term goals are typically achieved within six months and five years. They may have more specific deadlines than long-term goals. These goals include vacations, large retail purchases and recurring payments.

When setting short-term goals, make sure you have a plan that is specific and attainable. It’s important to plan ahead — even for something like buying a bike — so you aren’t left scrambling to make up for the sudden dent in your finances.

Long-term goals, on the other hand, are usually achieved after five years or more. They include things like retirement and paying off a mortgage. Long-term goals may not be as specific, and the timeline of the goal might be somewhat more flexible, but it’s still important to plan for these goals so they don’t end up getting neglected.

Additionally, because of the span of long-term goals, it’s important to revisit these goals at periodic intervals throughout your life. As changes in your life take place, such as getting a new job or starting a family, your goals might need some modification, and your savings plan will need to match that.

Examples of short-term and long-term goals

| Short-term goals | Long-term goals |

|---|---|

| Vacation | Retirement |

| Down payment for a car or house | Opening a business |

| Deposit for a new apartment | Paying for a child’s education |

| Recurring loan repayment | Buying a vacation home |

| Home improvements | Paying off a mortgage |

| A wedding | Paying off student loans |

You’ll likely have a combination of short- and long-term goals to balance. Work your goals around your usual expenses, focusing on needs like food and shelter first. Emergency and retirement funds are also high priority; contribute to these funds and pay off debt next. Then you can decide how to allocate the rest of your money toward your wants and other savings goals.

Know where you stand before you start to budget and save for your goals. Determine how much money you can spend and how much you can save per month based on your income. Use the 50/30/20 budget calculator as a starting point. Set a timeline for your goals, then work toward them.

Try to cut back on purchasing things you don’t need and set the savings aside for your goals. You might use some of this money immediately on short-term goals or to make a dent in your long-term goals.

Implementing Asset Allocation

Creating and maintaining a balanced investment portfolio requires careful consideration of asset allocation. It is, after all, more important than picking individual stocks in determining your overall profits. Choosing the right balance of stocks, bonds, cash, and real estate for your portfolio is a continuous process. As such, your aims should always be reflected in the asset mix.

We’ve listed a number of various asset allocation strategies below, along with an overview of their fundamental management techniques.

1. Strategic Asset Allocation

This method establishes and adheres to a base policy mix—a proportional combination of assets based on expected rates of return for each asset class. You also need to take your risk tolerance and investment time frame into account. You can set your targets and then rebalance your portfolio every now and then.

A strategic asset allocation strategy may be akin to a buy-and-hold strategy and also heavily suggests diversification to cut back on risk and improve returns.

For example, if stocks have historically returned 10% per year and bonds have returned 5% per year, a mix of 50% stocks and 50% bonds would be expected to return 7.5% per year.

2. Constant-Weighting Asset Allocation

Strategic asset allocation generally implies a buy-and-hold strategy, even as the shift in values of assets causes a drift from the initially established policy mix. For this reason, you may prefer to adopt a constant-weighting approach to asset allocation. With this approach, you continually rebalance your portfolio. For example, if one asset declines in value, you would purchase more of that asset. And if that asset value increases, you would sell it.

There are no hard-and-fast rules for timing portfolio rebalancing under strategic or constant-weighting asset allocation. However, a common rule of thumb is that the portfolio should be rebalanced to its original mix when any given asset class moves more than 5% from its original value.

3. Tactical Asset Allocation

Over the long run, a strategic asset allocation strategy may seem relatively rigid. Therefore, you may find it necessary to occasionally engage in short-term, tactical deviations from the mix to capitalize on unusual or exceptional investment opportunities. This flexibility adds a market-timing component to the portfolio, allowing you to participate in economic conditions more favorable for one asset class than for others.

Tactical asset allocation can be described as a moderately active strategy since the overall strategic asset mix is returned to when desired short-term profits are achieved. This strategy demands some discipline, as you must first be able to recognize when short-term opportunities have run their course and then rebalance the portfolio to the long-term asset position.

4. Dynamic Asset Allocation

Another active asset allocation strategy is dynamic asset allocation. With this strategy, you constantly adjust the mix of assets as markets rise and fall, and as the economy strengthens and weakens. With this strategy, you sell assets that decline and purchase assets that increase.

This makes dynamic asset allocation the polar opposite of a constant-weighting strategy. For example, if the stock market shows weakness, you sell stocks in anticipation of further decreases and if the market is strong, you purchase stocks in anticipation of continued market gains.

5. Insured Asset Allocation

With an insured asset allocation strategy, you establish a base portfolio value under which the portfolio should not be allowed to drop. As long as the portfolio achieves a return above its base, you exercise active management, relying on analytical research, forecasts, judgment, and experience to decide which securities to buy, hold, and sell with the aim of increasing the portfolio value as much as possible.

If the portfolio should ever drop to the base value, you invest in risk-free assets, such as Treasuries (especially T-bills) so the base value becomes fixed. At this time, you would consult with your advisor to reallocate assets, perhaps even changing your investment strategy entirely.

Insured asset allocation may be suitable for risk-averse investors who desire a certain level of active portfolio management but appreciate the security of establishing a guaranteed floor below which the portfolio is not allowed to decline. For example, an investor who wishes to establish a minimum standard of living during retirement may find an insured asset allocation strategy ideally suited to his or her management goals.

6. Integrated Asset Allocation

With integrated asset allocation, you consider both your economic expectations and your risk in establishing an asset mix. While all of the strategies mentioned above account for expectations of future market returns, not all of them account for the investor’s risk tolerance. That’s where integrated asset allocation comes into play.

This strategy includes aspects of all the previous ones, accounting not only for expectations but also for actual changes in capital markets and risk tolerance. Integrated asset allocation is a broader asset allocation strategy. However, it cannot include both dynamic and constant-weighting allocation since an investor would not wish to implement two strategies that compete with one another.

Asset allocation can be active to varying degrees or strictly passive in nature. Whether an investor chooses a precise asset allocation strategy or a combination of different strategies depends on that investor’s goals, age, market expectations, and risk tolerance.

Keep in mind, however, that these are only general guidelines on how investors may use asset allocation as a part of their core strategies. Be aware that allocation approaches that involve reacting to market movements require a great deal of expertise and talent in using particular tools for timing these movements. Perfectly timing the market is next to impossible, so make sure your strategy isn’t too vulnerable to unforeseeable errors.

Impact of Taxes on Investment Returns

Investors need to understand that the federal government taxes not only investment income—dividends, interest, and rent on real estate—but also realized capital gains.

There are expenses associated with every investment. Expenses beyond your initial investment amount could include commissions, fees, administrative costs, and taxes. Out of all the expenses, taxes might be the most painful and deplete your returns the most. But there’s good news, so don’t worry. Investing tax-efficiently can reduce your overall income and optimize your savings, regardless of your goal of generating cash flow or retirement savings.

The Schwab Center for Financial Research evaluated the long-term impact of taxes and other expenses on investment returns. Investment selection and asset allocation are the most important factors that affect returns. The study found that minimizing the amount of taxes you pay also has a significant effect.

There are two reasons for this:

- You lose the money you pay in taxes.

- You lose the growth that money could have generated if it were still invested.

Your after-tax returns matter more than your pre-tax returns. After all, it’s those after-tax dollars that you’ll spend now and in retirement. If you want to maximize your returns and keep more of your money, tax-efficient investing is a must.

Most investors know that if you sell an investment, you may owe taxes on any gains. But you could also be on the hook if your investment distributes its earnings as capital gains or dividends regardless of whether you sell the investment or not.

By nature, some investments are more tax-efficient than others. Among stock funds, for example, tax-managed funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) tend to be more tax-efficient because they trigger fewer capital gains. Actively managed funds, on the other hand, tend to buy and sell securities more often, so they have the potential to generate more capital gains distributions (and more taxes for you).

Bonds are another example. Municipal bonds are very tax-efficient because the interest income isn’t taxable at the federal level and it’s often tax-exempt at the state and local level, too.8 Munis are sometimes called triple-free because of this. These bonds are good candidates for taxable accounts because they’re already tax-efficient.

Treasury bonds and Series I bonds (savings bonds) are also tax-efficient because they’re exempt from state and local income taxes.910 But corporate bonds don’t have any tax-free provisions, and, as such, are better off in tax-advantaged accounts.

Here’s a rundown of where tax-conscious investors might put their money:

| Taxable Accounts (e.g., brokerage accounts) | Tax-Advantaged Accounts (e.g., IRAs and 401(k)s) |

|---|---|

| Individual stocks you plan to hold for at least a year | Individual stocks you plan to hold for less than a year |

| Tax-managed stock funds, index funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), low-turnover stock funds | Actively managed stock funds that generate substantial short-term capital gains |

| Qualified dividend-paying stocks and mutual funds | Taxable bond funds, inflation-protected bonds, zero-coupon bonds, and high-yield bond funds |

| Series I bonds, municipal bond funds | Real estate investment trusts (REITs) |

Many investors have both taxable and tax-advantaged accounts so they can enjoy the benefits each account type offers. Of course, if all your investment money is in just one type of account, be sure to focus on investment selection and asset allocation.

Asset Allocation in Different Life Stages

There is a common saying that every 5 years, 80% of people around you both in social and professional circles change. While it might not be true for everyone, this belief highlights something we all go through in our lives – change. From priorities to how we deal with situations, everything evolves. These changes in our lives also have a bearing on how we look at our money and investing.

Though every individual is different, the asset allocation lifecycle can basically be broken down into four categories.

- Early Career Stage

Beginning investors launching their careers tend to have the highest bandwidth for potential risk. The key at this stage is to have financial independence before these risky investments can be made. Make sure you are free of outstanding debt and have a substantial budget first, before making any moves. This is also an ideal time to start a company 401(k) or an individual retirement account (IRA) and enjoy the ensuing tax breaks well into the future.

- Mid-career Stage

Your mid-career stage is all about balancing growth and risk management as your family, expenses, and salary begin to grow. Explore different strategies that incorporate diversification and asset classes with more stability, such as bonds and real estate. A moderate amount of risk can still be taken in these pre-retirement years. So, find a balance between riskier investments like stocks and more dependable sources of future returns.

- Pre-retirement Stage

The financial moves you make in the pre-retirement stage are very much dependent on the planning that occurred in the years and decades before. If you procrastinated saving for retirement or simply didn’t have the excess funds to do so, now is the time to buckle down. If you have a healthy portfolio, then it’s time to build. The key is managing risk and preserving your capital, regardless of your personal scenario, while exploring new or revised strategies to increase your future income.

- Retirement Stage

By your retirement stage, you have likely completed most of your financial responsibilities. You will have multiple sources of income from your investments, Social Security or other retirement benefits, and other assets. The best strategy at this stage is to make withdrawals smartly to fund your retirement years and bolster the assets that your loved ones will eventually inherit. Make sure that you are taking the required minimum distributions from your retirement accounts. Also, use the bucket approach – or withdrawing from different buckets to serve different purposes – to keep your wealth primarily intact.

We as human beings resist change. Suppose you are a bachelor and spending quite a good amount of money on yourself. But, all of a sudden you are married and your responsibilities have increased. Now, if your income is nearly the same as it was during bachelorhood then you will need to cut down your expenses. And this shift from one stage of life to the other can be difficult. Hence, keep in mind that none of these changes should be sudden.

Life-stage planning can ensure a smooth and gradual transition from one life stage to the other. To that end, you can create a model portfolio for every life stage. Do take into account the variable factors we discussed earlier. For instance, if you are salaried and your company is doing reasonably well, then your income is stable. But if your company or sector is not performing well, there is a bit of uncertainty even as you are a salaried employee. Therefore, the portfolio and investments will be different in both cases.

Another important factor to consider is to take your family members along. An increase in your salary may raise their expectations on how they want to live. In such a scenario, It is important to explain the need to maintain your savings rate. And how it can be crucial in securing the future.

Conclusion

Diversification is the basic premise of asset allocation as investable asset classes are decided based on goals and risks, and the need to mitigate portfolio volatility. The main goal of asset allocation is to minimize volatility and maximize returns.

The process involves assessing your risk/return profile and then investing money in a certain proportion of asset categories that do not all respond to the same market forces, in the same way, at the same time. Asset allocation will vary from one investor to another. For example, an aggressive investor can have 75% in equity mutual funds, 20% in fixed-income funds, and 5% in gold.

Asset allocation can impact an investment portfolio in four key ways:

- Optimise Returns: every asset class will generate different returns and react in a dissimilar manner to similar market conditions. Therefore, by spreading investments across asset classes, an investor can optimize portfolio returns.

- Minimise Risks: risk inherent in all investments. However, in some investments, the risk is high while in others it is low. Asset allocation ensures that the portfolio is diversified and that portfolio risk is spread across asset classes.

Since each asset class performs differently in various macro and microeconomic environments, it is important for investors to build a diversified portfolio and allocate investments to multiple assets.

Generally, an investor’s ability to absorb risk is inversely proportional with his age. This means that the younger an investor is, the better is his ability to absorb risk. Consequently, investors just starting off on their investment journey can allocate a higher proportion of their assets to equities. This diminishes as the investor ages.

Asset allocation, once achieved, should be periodically reviewed and re-aligned, if needed, depending on changing circumstances and needs.